In the early 40’s, our country was still trying to shake off the devastation of the Great Depression. Whole sections of Rural America were still not yet Electrified, nor did they have telephone service, or highways for that matter. For those Americans who had electricity, listening to the radio was their link to the outside world.

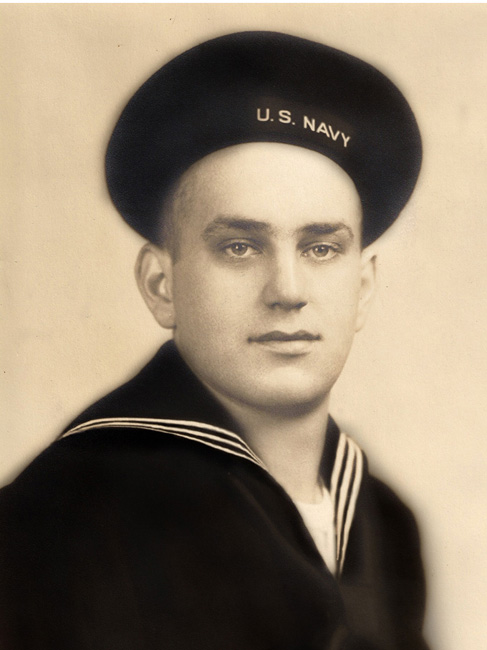

Hundreds of thousands of kids, still wet behind the ears, flocked to recruitment centers everywhere to join in the fight against our enemies in Europe and in the Pacific (Japan). Young men who never been away from home — never been off the farm or out of the hills were now training to be soldiers and sailors. Imagine finishing boot camp with orders to ship off to Boston for assignment. A new ship was almost ready there. Maybe you take a train to New York City en route to Boston. After a night in the Big Apple, you take a train north to Boston. You see the ocean for the first time in your life.

Months later, after making trial runs up and down the eastern seaboard, you transit the Panama Canal – you can hardly believe such a thing could exist. Later, you arrive in Pearl Harbor. Two years after the Sneak Attack, you are stunned to see sunken ships still spewing oil. You berth up next to the Battleship Arizona. Her upper gun turrets still stick up out of the water. More than a thousand dead sailors are forever entombed below within her bulkheads.

After joining up with dozens of other warships into a Task Group, you head off across the VAST Pacific into an unknown and uncertain future.

After the Boston spent half a year ranging up and down the coast of Japan on Occupation / Demilitarization Duty in the Fall of 1946, she steamed back to California and most of the remaining crew left the ship. Then she headed north to Bremerton and joined the “Mothball Fleet.”

From commissioning in Boston to retirement in Washington three and a half years later, the “Mighty B” traveled 286,000 nautical miles – 330,000 land miles for all you drivers out there.

No wonder the guys didn’t talk about it much after the war.

Steve