In my early research prior to writing A Bird’s Eye View, I was struck by the magnitude of the logistics of the Pacific War — the moving of men, equipment and materials. For example, Task Force 58 (and TF38) was a collection of 97 warships that ranged widely all across the Pacific, attacking enemy bases over hundreds of thousands of square miles of ocean. There were about 100,000 men aboard those ships.

When the Task Force combined with other fleet components for the invasion of Iwo Jima, for example, there were more than 650 ships steaming toward that tiny volcanic island — ferrying Marines and equipment in a massive armada.

At some point, I read that it took one metric ton of materials per man per month to prosecute this war. The Navy (combined Navy, Naval aviators, Coast Guard and Marines) totaled over 3,000,000 men (and yes, there were some women). [We’re not even factoring in the ARMY and all the other personnel involved in the Pacific.] Thirty six million metric tons of fuel, bombs, food, equipment and supplies a year flowing across the U.S. and over the waves . . .

——————–

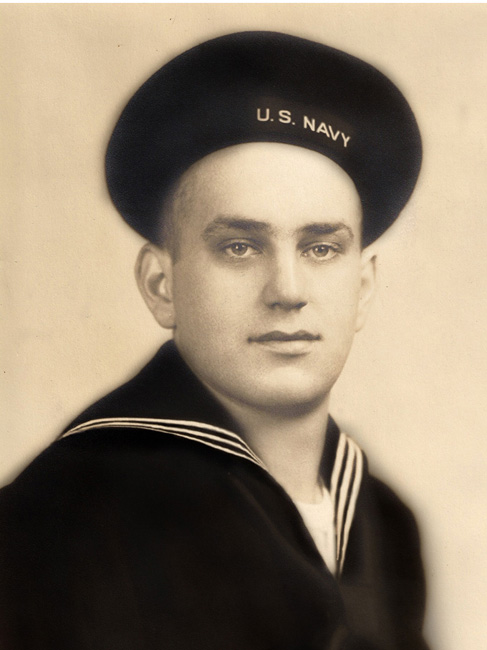

I was lucky to receive my late uncle Wilson’s “Navy stuff” a few years ago from his wife, my aunt Marge. Wilson was a coxswain aboard the destroyer Erben during the war. The Erben was mostly attached to the Seventh Fleet, also known as “MacArthur’s Navy” and had about 100 men aboard. Their duty was mostly screening the Invasion Fleet that delivered Marines and Infantry soldiers to their destinations.

I have some of the ship’s newsletters. Gleaned from the 1 year Anniversary issue (5/28/44): [Engineering] “During its first year, the ERBEN traveled 68,964.7 miles at an average speed of 15.8 knots.” “We consumed 3,082,056 gallons of fuel oil, at an approximate cost of $88,000.” “Every man on board uses almost 20 gallons of fresh water a day.” [Communications] “The Radiomen and Signalmen have used up 50,000 message blanks” [Supply] “The Supply Division has prepared and served 328,425 individual meals at a cost of $71,427.03.” “339 tons of food have been consumed.” [Ordnance] “We have fired 3,420 rounds of 5”/38 ammunition [5” guns], 7,834 rounds of 40mm, and 12,694 rounds of 20mm ammunition [anti-aircraft] . . . The total expenditure on ammunition was $328,537.50.” [C & R] “While in drydock [6 times], four and one third tons of anti-fouling paint have been applied to her bottom . . . the paint would completely cover five and one-half football fields.”

In a future blog, I will share comparable stats about the Boston, gleaned from the first year anniversary issue of the weekly newsletter The Bean Pot, sent to me by the family of Seaman 1st Class Augustus Harris.