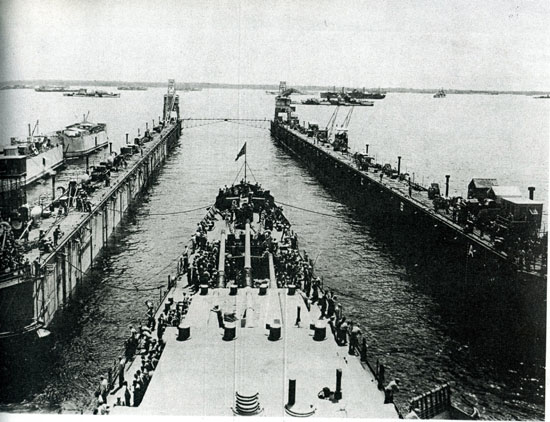

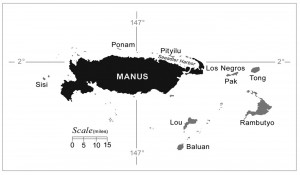

The ships of Task Force 38 were east of the Northern Philippines by December 13 to begin support of the Mindoro Landing. The strategy was to blanket Luzon with round-the-clock fighter coverage over the airfields of Luzon — squashing kamikaze attacks before they could materialize against the US Invasion Fleet off Mindoro.

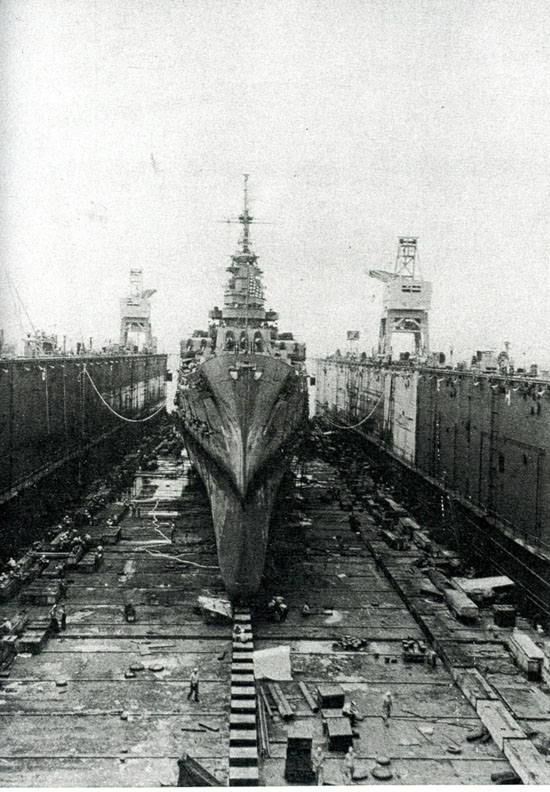

Admiral Halsey ordered the ships to a refueling rendezvous starting early Sunday morning, December 17. After three days of raids and attacks against Luzon, the ships were low on fuel – especially the destroyers. TF38 ships met up with the Service Group — oilers, escort carriers and their destroyers, but the wind and seas were kicking up and refueling had to be called off. over the next twenty four hours, three more refueling rendezvous were scheduled, but none could be exercised. The men and ships were seasoned by several typhoons since heading to Pearl Harbor a year earlier. They had endured many days of foul weather. No one on the ship was prepared for the monstrous storm that was now heading their way, however.

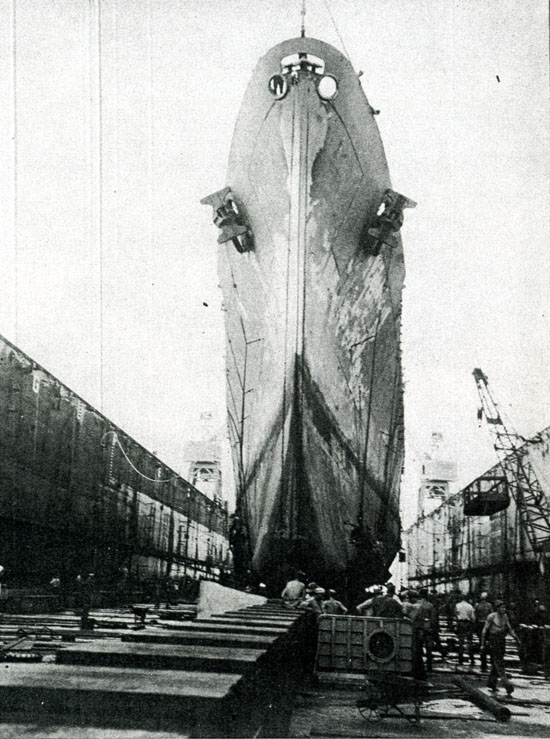

A fierce, tight, fast moving storm had began developing days earlier a thousand miles away and went undetected by traditional weather observations in place at the time. Despite each aircraft carrier having aboard a meteorologist, the storm eluded detection until it was too late. By nightfall on the 17th, the ships were struggling against giant waves and fierce winds, and were scattered across sixty miles of ocean. Mighty aircraft carriers were bobbing down so low that they scooped sea water across their decks. Planes broke free and crashed into each other or were swept into the sea. The destroyers, most dangerously low on fuel and de-ballasted, were at the mercy of waves taller than their ships and at times, winds that gusted past 100 mph.

This is what the men of the Boston endured on that awful night between Dec 17 and December 18. The ship recorded side-to-side rolls that went way beyond the danger-point.

Halsey had continually ordered the ships on a southerly course, because his “weather guys” thought the eye of the storm was a hundred miles to the east. This would take them south of the worst part of the storm, and would allow the ships to refuel in calmer waters. In fact, though, the eye of the storm passed right through the formation of ships, causing some to be whacked on all sides, making navigation impossible. Most ships lost power and/or radio, and visibility was zero. During that awful night, three destroyers went down: the Hull, the Spence, and the Monaghan. Total loss of life: almost 800 men — mostly sailors aboard the three destroyers, but also includes men swept off other ships throughout the storm.