9/2/17

Not all Task Force ships could fit into Tokyo Bay for the historic day. Many of the warships that had endured all those Battles and Campaigns were stacked up in Sagami Wan Bay outside of Tokyo Bay waiting for a “spot” to drop anchor and bear witness to the Signing of the Articles of Surrender. The day was rife with politics and political decisions – not the least of which was the presence of General MacArthur, the polarizing character who was a threat to run against Harry Truman in the next election. The selection of the Battleship Missouri (the johnny-come-lately that entered the Pacific War just in time for Okinawa) – Harry Truman’s home state . . . and last, but not least, the British task group ships, who finally got around to go the Pacific and joined TF58 – around the same time as the Missouri (mop-up duty).

No room for the Boston.

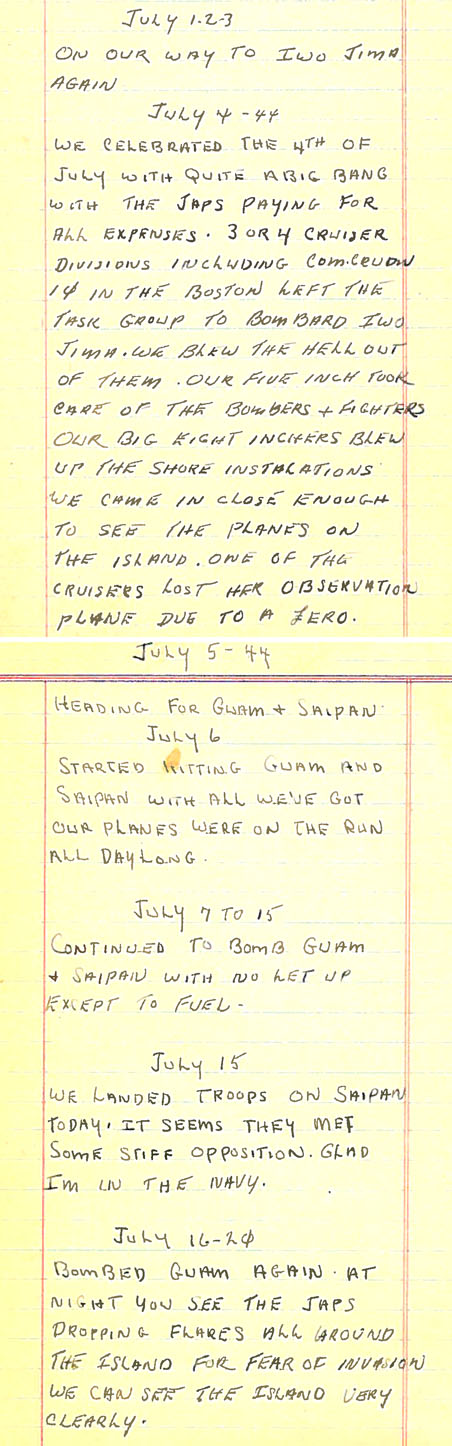

Putting politics aside, I smile as I transcribe Frank Studenski’s diary entries for the couple of days leading up to the 2nd:

August 31, 1945 Today is another normal day. This bay is filled with the Pacific fleet. This afternoon some of the ships weighed anchor and entered Tokyo Bay.

Anchored in Sagami Wan before entered Tokyo Bay [sic], the off duty watch had movies on the fantail at 1800 hours. May watch was on Quad 5. We were still on Condition Three and I was Gun Captain, I wanted to see the end of the movie and told the phone talker to stay awake, if air defense checks the quads. I went back to se the end of the movie and about a half hour later my name was called over the P.A. and was told to report to the quarter deck on the double. The phone talker fell asleep and air defense could not raise Quad 5. I was given a deck court martial for violating General Order #5 (I shall not leave my post without being properly relieved.) I was given ten days breqad and water with full rations every three days. I’ll never forget those ten days.

September 1, 1945 Almost half the ships left here and are now anchored in Tokyo Bay.

September 2, 1945 Today is “V. J. Day” with the signing of the Peace Treaty. I am looking forward to some liberty in Tokyo.