Veterans Day, 2016

(If you’re reading this and don’t know who George Pitts was, read the Baked Beans books.)

Blog about the sailors in WWII who served on the USS Boston

Veterans Day, 2016

(If you’re reading this and don’t know who George Pitts was, read the Baked Beans books.)

11-5-16

The US Navy’s contribution to freeing the Philippines from their Japanese Occupation began in earnest on September 1, 1944, when Task Force 58 became TF 38, systematically attacking enemy positions, and supporting a whole series of Landings across the Archipelago by Marines and Army troops. For all intents and purposes, Operation King II ended on November 11, 1944 when the fleet anchored in Ulithi.

Can someone give that crazed revisionist Filippino President Duterte a history book, please?

Anyway, at the end of October 1944, Japanese defensive strategy, Operation Sho Go 1 was implemented and developed into The Battle for Leyte, (also known as the Second Battle of the Philippine Sea.) The battle developed over several days and is generally though of as having four distinct actions: Sibuyan Sea, Surigao Strait, Cape Engano, and the Battle off Samar. Part of the plan called for Admiral Ozawa to cruise south with a task group of (mostly) carriers in order to lure Halsey into breaking up TF38 so that he could steam north to engage the carrier fleet. Naturally, Halsey took the bait and did exactly that. History shows that his decision, sometimes derisively called The Battle of Bull’s Run didn’t change the course of the War much, one way or the other.

Masanori Ito had this to say about the outcome: RUINOUS DEFEAT The Japanese defeat at the battle of Leyte Gulf was indeed miserable. Losses came to 3 battleships, 4 aircraft carriers, 9 cruisers, 13 destroyers and 5 submarines, for a total of 34 ships; while the enemy lost only four. The score was one-sided to an extent rarely seen in warfare. It was complete revenge for Pear Harbor.

10-22-16

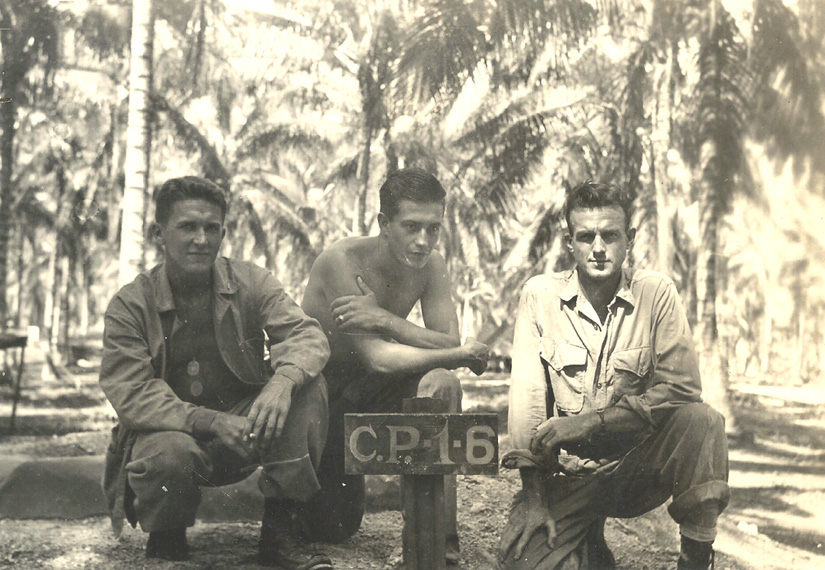

Readers of my book will recognize the Commanding Officer of the USS Boston Marine Detachment, Norm Bayley. Norm joined the ship late in the War. For a refresher on Norm’s story, check out Vol 3 of Baked Beans.

Norm was a student at Santa Clara University, when his pal, Will McDonough talked him into signing up for the Marine Corps Reserves. Norm was asked several times where he wanted to serve, always answering “Air Corps.” After his training in Camp Pendleton, he found himself aboard a cruiser, bound for the invasion of Guadalcanal. He endured all the horrors that unfolded on that island. Once there, he learned that his pal McDonough (who was actually in the Air Corps), was one of the pilots on Guadalcanal. Japanese ships bombarded the island every night, and one night the saw the distant airfield go up in a massive fireball. He lost his best friend in that attack.

Norm contracted malaria. His condition was so bad they shipped him off to New Zealand, from whence his body would be shipped back to the States. Miraculously, he did not die in New Zealand, and eventually found himself in an experimental malaria treatment facility in Klamath Falls, Oregon. All the while the Boston was engaged in the many battles of the War in the Central Pacific, Norm fought off bout after debilitating bout of deadly malaria.

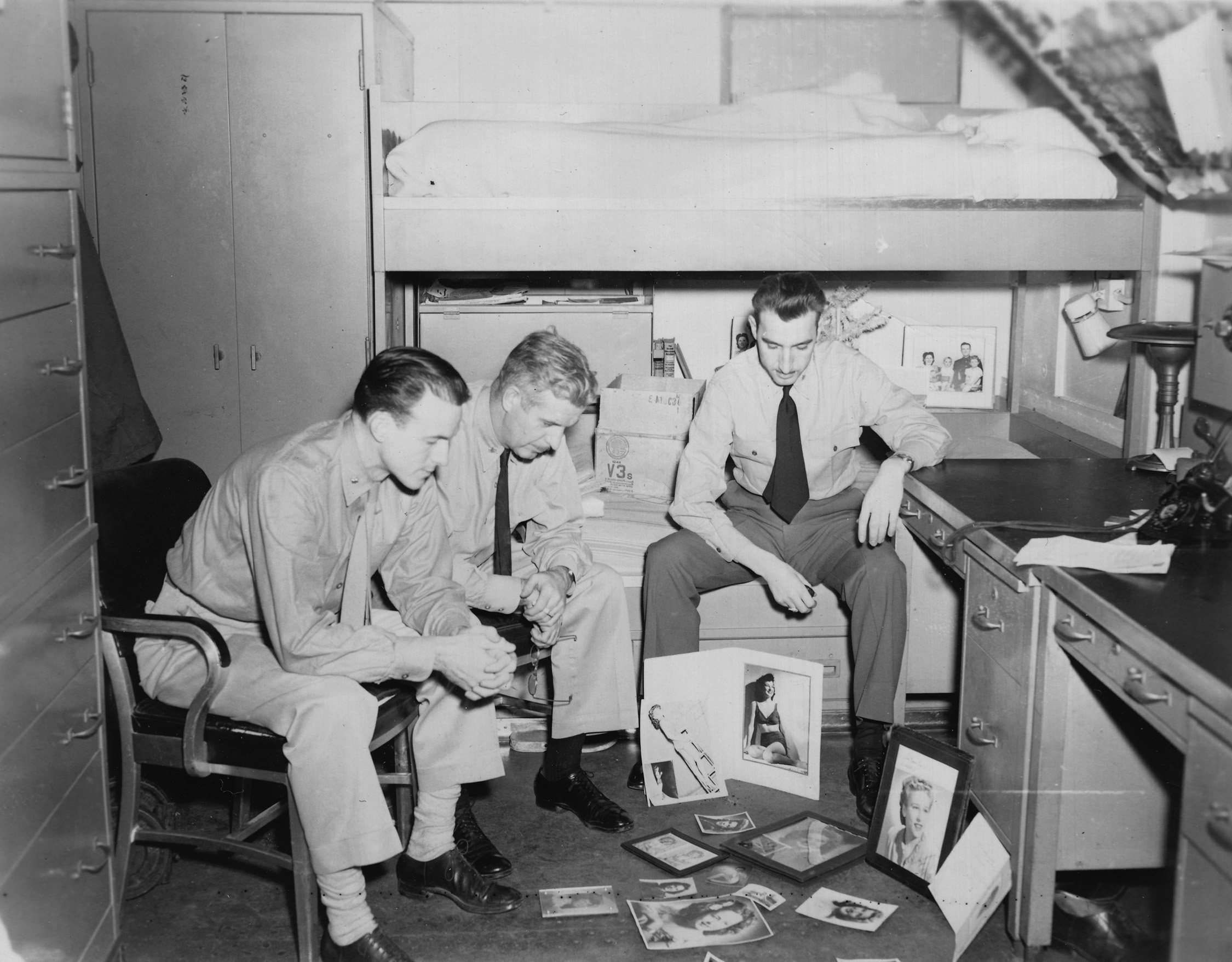

Finally deemed “fit for duty,” Norm was assigned to the Boston, replacing the CO of the Marine Detachment. In July of 1945, Norm flew to Pearl Harbor, then to Kawajalein where he boarded one of the Service Ships of TF 30, steaming east to join up with Task Force 58 in their final push against the Home Islands of Japan. (For Norm’s remarkable stories, take a few minutes to re-read about Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Surrender of the Kamikaze Training Base at Katsuura in Baked Beans Vol 3). Norm played significant roles in the Occupation of Japan, including setting up a major Marine Base Camp at Kure. {Someday, I hope to add a Vol. 4 to Baked Beans — focusing just on Occupation Duty.}

Norm Bayley turned 99 last week.

steve

10-13-2016

Posts over the last several years have detailed many aspects of the Battle off Formosa and the subsequent torpedoing of the Canberra (Oct 13), followed by the Houston (Canberra’s replacement in Task group 38.1) being torpedoed not once (first on Oct 14) but twice (then again on Oct 16).

In The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Chapter 7, The Battles for Leyte; Phase One, author Masanori Ito writes: . . . enemy air attacks hit Formosa, beginning 12 October, and depleted the strength of the Sixth Base Air Force. These air battles were reported at home as great victories for Japan, but nothing could have been further from the truth. Fukudome’s air strength suffered such losses in these enemy attacks on Formosa that it was rendered useless for the Sho operation. [Operation Sho 1 was designed to counter any enemy attempt to invade the Philippine Islands.]

Of the crippling of the American cruisers in the Philippine Sea off the coast of Formosa, Ito continues in the next chapter: Complications began in mid-October with the attacks on Formosa by Admiral Halsey’s fast carrier striking forces. The air battles off Formosa, according to the reports of surviving Japanese pilots, were a great victory for Japan. The cumulative results of these reports indicated that one dozen capital ships of the enemy had been sunk and another two dozen heavily damaged. On the basis of these reports, it was judged that the enemy would not soon return. In reality, only two enemy cruisers had been damaged, while Japan suffered the loss of 174 planes. These air battles, were, in fact, a great victory for the enemy.

On the basis of these erroneous reports, Admiral Shima’s fleet was ordered out to pursue the fleeing enemy south of Formosa, and to rescue downed pilots. Shima’s ships were selected because of their high speed and mobility. As Shima approached the scene of his intended “mopping-up operation,” however, he was astounded to find two gigantic naval forces, in perfect battle order. [ Ito is describing Halsey’s “Streamlined Bait” mousetrap . . . the Boston and it’s small task unit was “dangled out” as bait to lure the enemy fleet to come within range of the Cripples to finish them off. However, within a hundred miles of the Cripples, he waited for the enemy with two of his four task groups – carrier planes gassed and loaded with bombs; capital ships on General Quarters ready to unload their five and eight inch guns. ] His ships could not last five minutes against such an enemy. Admiral Shima wisely ordered a course reversal for his cruisers and destroyers and, at flank speed of 34 1/2 knots, headed for Amami Shima and comparative safety.

10-8-16

In late September, task force planes were bombing Leyte in preparation for the upcoming invasion. The Boston spent the last five days of the month anchored in Eniwetok. On Oct 1, the ships headed west toward Okinawa to begin a systematic reduction of Japanese aircraft in bases that could be used against American assault troops. The task groups hit a typhoon, and for several days they were unable to launch any planes. On October 10, after refueling the day before, they launched planes against Okinawa.

I have mentioned many times over the years that the Japanese had a series of defense plans to counter American advances – all designed to be crushing defeats of the Americans as they advanced across the Pacific.

From The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy by Masanori Ito* Following the defeat in the Marianas in mid-June 1944, Japanese planners had estimated that it would take eight months for the Navy to be back in fighting trim. In just half that time Combined Fleet was obliged to sortie with all available forces. It was shattering to naval staff men when Operation Sho 1 had to be activated so precipitously on October 18, after scarcely three months of training at Lingga [Lingga Roads, near Singapore, was where the Japanese Navy relocated after Task Force raids drove them from the “impregnable fortress” of Truk (Carolines)]. Yet has they stopped to think of it, in view of the amazingly rapid advances the enemy had made in the third year of the war, the Japanese Navy was fortunate to have had even that long for a breathing spell.

Operation Sho 1 was designed to counter any enemy attempt to invade the Philippine Islands. Its tasks may be summarized as follows:

All the above factors played out over the rest of October and the Boston was in the middle of all this as both the Battle Off Formosa and Battle for Leyte Gulf (the Second Battle of the Philippine Sea) unfolded.

*The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy by Masanori Ito English Translation copyright 1962 by WW Norton Company