I’ve started an ambitious project to create a record of information about each sailor on the USS Boston during World War II. I Started with a list that my brother Steve gave me from Frank Studenski’s materials. What I found out was these records were taken as a snapshot in time near the end of the war. This was one of my motivations for my NARA trip to Washington DC. I was able to find a microfiche of USS Boston Personnel records during world war II. I photocopied the commissioning records for enlisted men and I’ve been working through these records by placing them in a database; once I enter a sailor his record is live on the website. Subsequently I received a copy of the microfiche.

So when you click on the link to crew list you can find ‘Frank J Abbatantuono’, when you click his name, you’ll see his record as I’m entering it; next to frank you’ll find ‘ABELL, W.H’ and when you click on this link it will tell you he’s not yet entered into our database, since I only have his name at this time (I hope to be catching up to Seaman Abell, probably transferred at Ulithi).

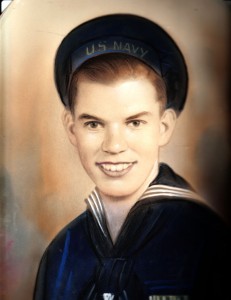

Currently, since April, I’ve entered over 1/2 of the enlisted sailors on the commissioning day. I’m plugging along slowly. Once the commissioning day is over, I have complete records for discipline, promotions and transfers to and from the Boston as the war proceeded. So right now all you’ll see if the sailor is in the database is that the sailor arrived on June 30, 1943 and is a plank owner. In the future you’ll see disciplinary actions, sick or injury reports, promotions and transfers. I’m hoping to add a picture of the sailor and in the future maybe we could get some biographical info from after they left the navy.

I started with about 1600 names, and currently I have just shy of 1900 names; I expect we’ll have about 2,500 to 3,000 sailor names in our database when we are complete.

Please check out the link to the crew list and let us know what you think.

Bill