10-5-19

A recap of Boston’s station in the task force(s): Task Force 58 (and 38) was organized into a flotilla of warships. There were destroyers, cruisers, battleships and aircraft carriers – typically around 100 ships. In order for a large Task Force to carry out it’s objectives, it was broken down into smaller “task groups.” Each task group was built around several carriers, and each carrier was surrounded by “screens” (a screen = a group of ships whose purpose was to protect the carriers.) Carriers were surrounded by a screen of “capital ships” – (battle wagons and cruisers), capital ships were screened by a ring of destroyers – first line of defense against enemy ships and aircraft. A typical task group had 4 aircraft carriers, surrounded by a ring of large capital ships ( usually 6 or more), surrounded by a “picket screen” of destroyers – usually 12 or more.)

For example: TG 38.1 (near the end of Philippines Operations and through “Operation Gratitude” – South China Sea and French IndoChina) consisted of 4 aircraft carriers (heavy carriers Yorktown, Wasp and Essex, and light carrier Cowpens), screened by 2 battleships (Massachusetts and South Dakota), 3 heavy cruisers (Boston, Baltimore and San Francisco), 2 light cruisers (Santa Fe and Flint), screened by two destroyer divisions (Cushing, Uhlmann, Colahan, Halsey Powell, Benham, Yarnall, Twining, Wedderburn, Stockham, DeHaven, Mansfield, Lyman K Swenson, Collett, Maddox, Blue, Brush, Taussig and Samuel N. Moore. 29 warships, by my count. 25 of those ships were there to protect the carriers.

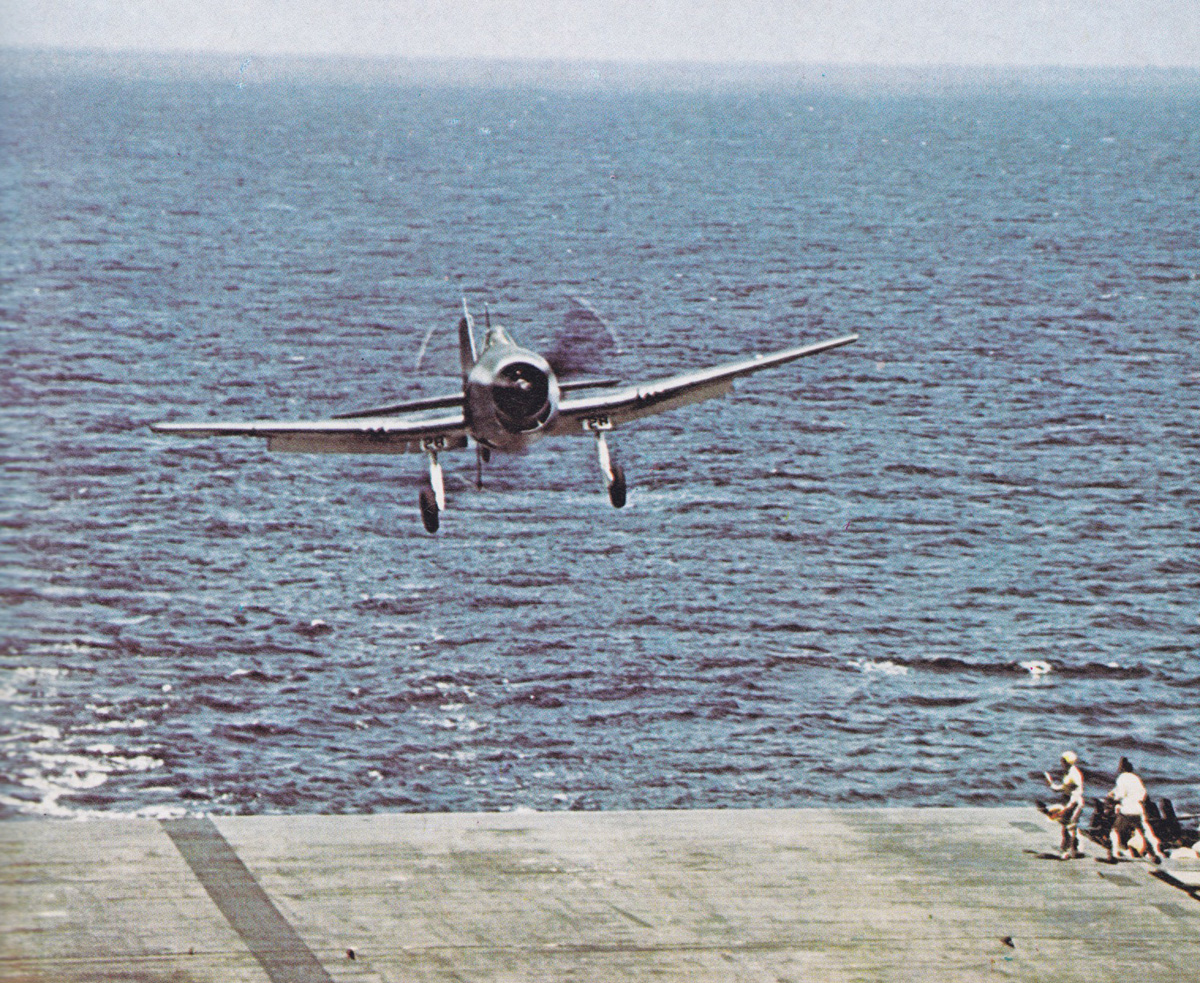

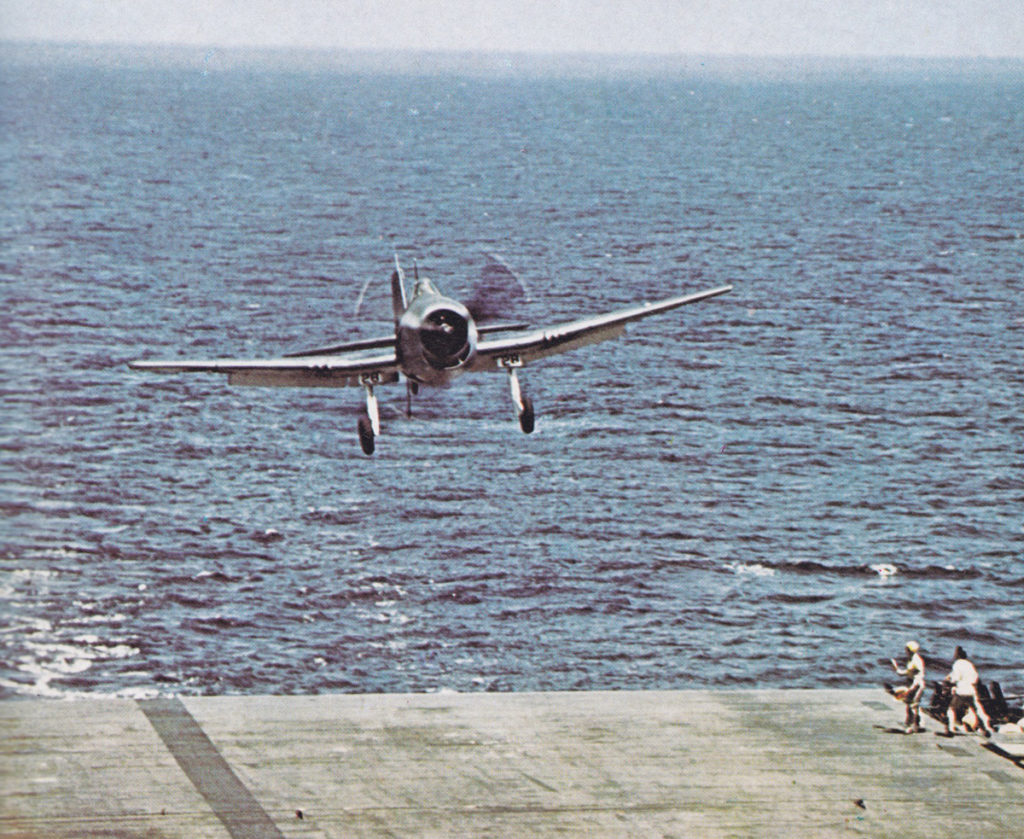

Every ship’s job was to play a role in securing the viability of the main asset in the war in the Pacific: carrier planes.

steve