Update

11/3/19

Over the last year or so, several factors that influence this web/blogsite have occurred / changed. As you probably know, we were hacked – the attacks came in through our email links, causing many headaches for Bill, as he worked diligently to build new protections. As a result, we had to suspend auto alerts of new posts to those folks who had requested them.

We also put up another site about Task Force 58 / 38. (www.taskforce58.org) – a work in place, but “unfinished.”

At Bill’s prodding, we put up a Facebook Group Page USS Boston CA-69; there are currently 78 members. Oftentimes, I post the blogs from the original website (https://ca-69boston.org) onto the Facebook page – but not always. Sometimes there is material that appears in one place but not the other.

Which brings me to the final bit: me. Regular readers of this site will have noticed my blogs have been less frequent of late. The reason: I have been immersed in writing something that I’ve wanted to do for 30 years. I side-tracked it for many reasons (not the least of which was the Boston books and the websites). I won’t reveal what it is exactly – but it involves a piece of colonial history that “changed everything.” I have not walked away from the Boston, but until I finish what I started, my contributions will be less frequent.

Peace.

Steve

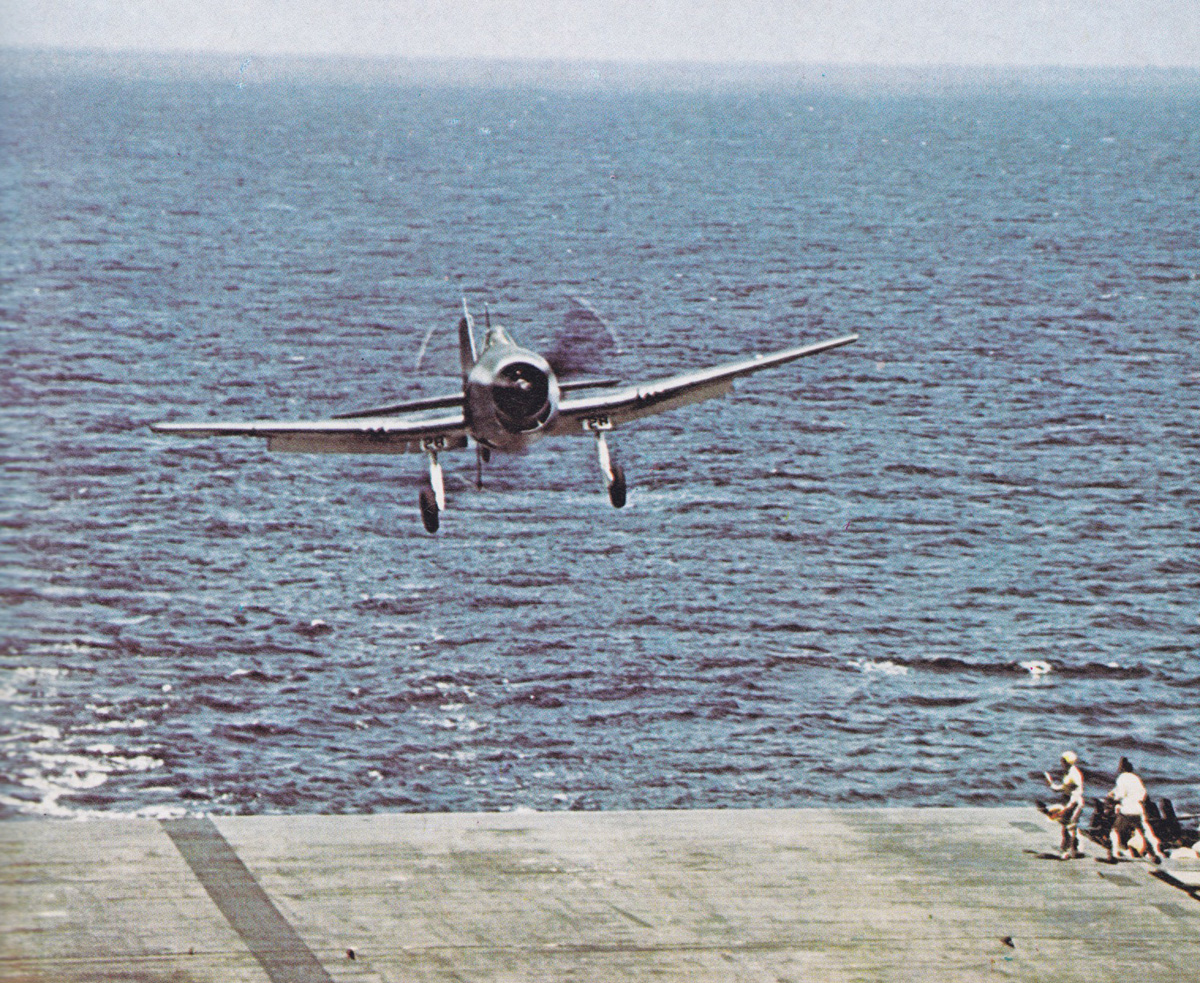

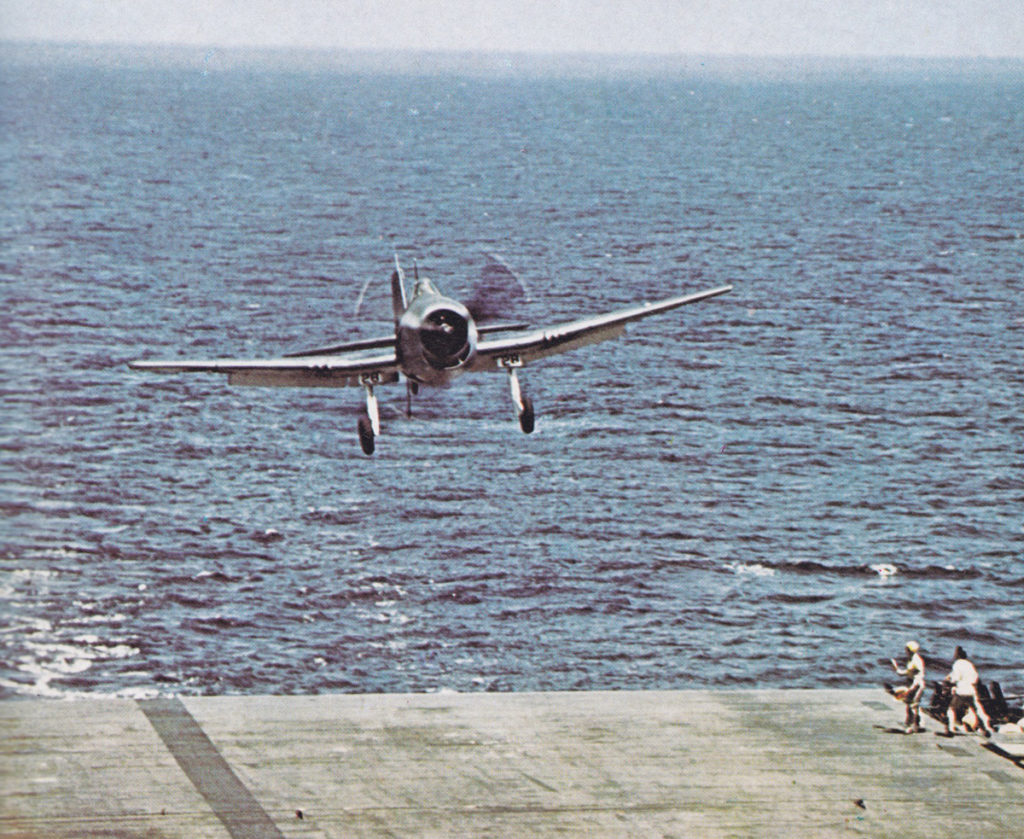

carrier planes

10-5-19

A recap of Boston’s station in the task force(s): Task Force 58 (and 38) was organized into a flotilla of warships. There were destroyers, cruisers, battleships and aircraft carriers – typically around 100 ships. In order for a large Task Force to carry out it’s objectives, it was broken down into smaller “task groups.” Each task group was built around several carriers, and each carrier was surrounded by “screens” (a screen = a group of ships whose purpose was to protect the carriers.) Carriers were surrounded by a screen of “capital ships” – (battle wagons and cruisers), capital ships were screened by a ring of destroyers – first line of defense against enemy ships and aircraft. A typical task group had 4 aircraft carriers, surrounded by a ring of large capital ships ( usually 6 or more), surrounded by a “picket screen” of destroyers – usually 12 or more.)

For example: TG 38.1 (near the end of Philippines Operations and through “Operation Gratitude” – South China Sea and French IndoChina) consisted of 4 aircraft carriers (heavy carriers Yorktown, Wasp and Essex, and light carrier Cowpens), screened by 2 battleships (Massachusetts and South Dakota), 3 heavy cruisers (Boston, Baltimore and San Francisco), 2 light cruisers (Santa Fe and Flint), screened by two destroyer divisions (Cushing, Uhlmann, Colahan, Halsey Powell, Benham, Yarnall, Twining, Wedderburn, Stockham, DeHaven, Mansfield, Lyman K Swenson, Collett, Maddox, Blue, Brush, Taussig and Samuel N. Moore. 29 warships, by my count. 25 of those ships were there to protect the carriers.

Every ship’s job was to play a role in securing the viability of the main asset in the war in the Pacific: carrier planes.

steve

Just the facts, ma’am.

9/28/19

Everyone who knows anything about WWII knows about Japanese Internment Camps. Everyone reading this post, I’m sure, has an opinion about this chapter in our history: some think it was the right thing to do (under the circumstance), others think it was the entirely wrong thing to do. I’m not writing this to fish for your feelings on the matter. The fact is – it happened and it doesn’t matter one iota whether we think it was right or wrong. That’s the thing about history. Stuff happened. Lots of stuff, over long periods of time. And stuff is repeated – over and over and over again.

So, the Japanese camps . . . Let’s go way back in the Way Back Machine (Sherman). Now, this is a long and very complicated story in our history, so I’m gonna condense the hell out of it. In Colonial New England, in 1675 to be exact, there were two groups of people: Natives and European settlers. The Europeans in New England were almost entirely from England – a trend that started 50 years earlier with the first Pilgrims. The Natives, while all being Algonquin speakers (from scores of tribes) could be broken down into two groups: Indians still living in the “traditional ways”, and Indians who were converted to Christianity, the so-called “Praying Indians.” Those missionized Indians were relocated to “Praying Villages” and were encouraged to “live like English.” The most notable village: Natick, Massachusetts.

Peaceful co-existence that glued colonists and Indians together from the time of Massasoit and the Pilgrims unraveled completely over 50 years, culminating in Massasoit’s own son “Philip” leading a devastating armed rebellion against the colonies. The Colonies were immediately rattled, and military and civilian leaders scrambled to do everything they could to give themselves an edge. One solution: they rounded up all the Praying Indians, fearing they would help or join the natives, and led them off to “containment camps” across southern New England, in the late fall of 1675. The most notorious was Deer Island in Boston Harbor, a treeless island onto which at least 500 Indian men, women and children were dumped without any food and very little shelter. Christian missionary John Eliot was perhaps, the only colonist to visit, and he was terribly horrified by what he saw. Lacking food, shelter, clothing and clean drinking water, most died within the first few months of “containment.”

steve

Fu-Go. Surprise.

9-7-19

Podcasts. I have mixed feelings about them. There’s a million of ’em out there, and I never really feel that I have time (patience?) to listen to podcasts. Over time, however, a few of them have slipped into my little orbit, and every time one does, I think/say: Damn. I should listen to more podcasts! Case in point: the Dan Carlin Hardcore History podcasts – especially about WWI and WWII. Like a war, however, listening to one of his podcasts is a bit like being “under siege.” You need a LOT OF TIME to devote to one of his podcasts; although they are most interesting and definitely worth it (if you have the time.)

A friend of mine recently texted me a Radiolab podcast (WNYCStudios) titled Fu-Go. It’s a mere 35 minutes long! I highly recommend it. It’s fascinating, and I promise you that you never learned this in history class.

https://player.fm/series/radiolab-from-wnyc/fu-go

Tell me what you think.

steve